Rethinking Darwin’s Naturalisation Conundrum through Spatial Lenses

Darwin’s naturalisation conundrum has long puzzled ecologists. Two competing ideas – preadaptation and limiting similarity – offer contrasting explanations for why some introduced species thrive while others fail.

The former suggests that invaders succeed when they resemble native species, benefiting from shared traits suited to local conditions. The latter argues that similarity breeds competition, so success favours difference. Both sound plausible, yet evidence has remained inconsistent.

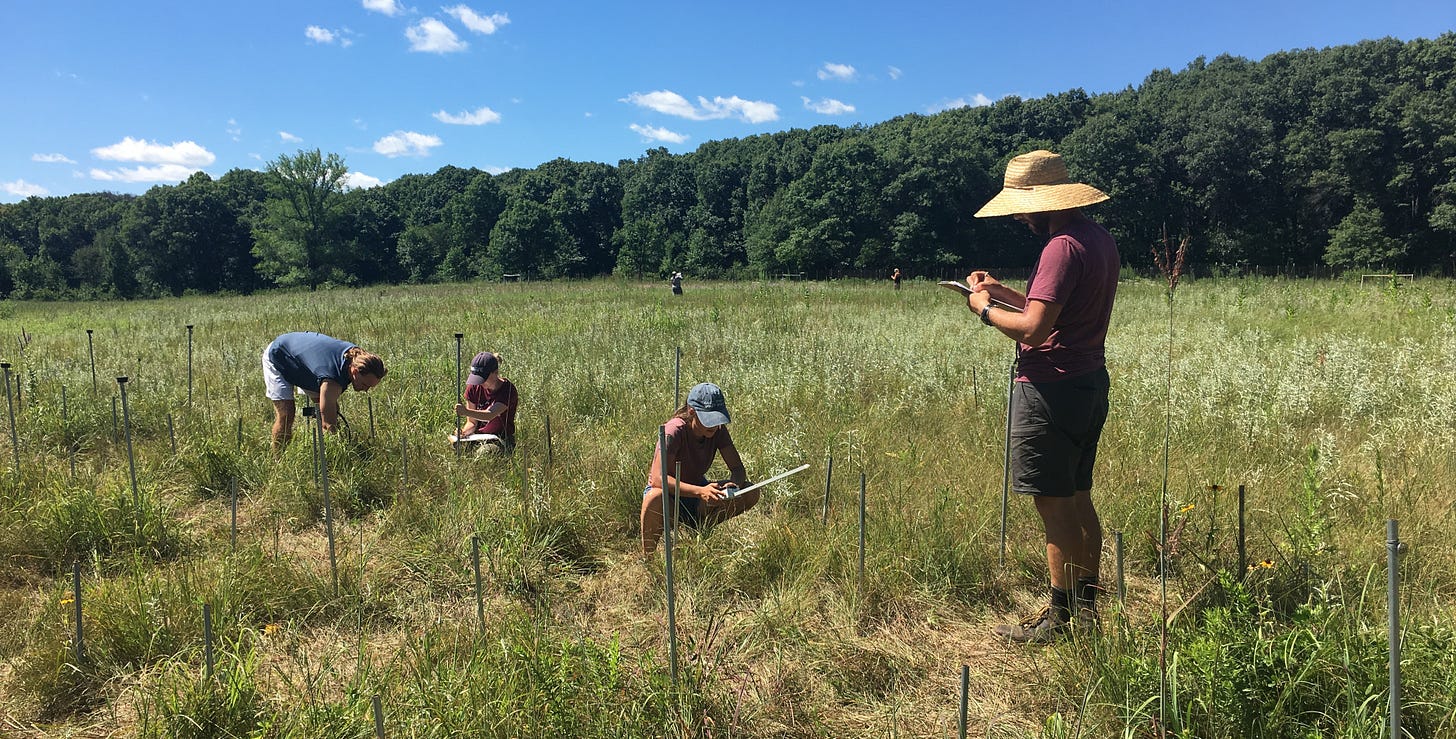

A recent study led by Maria Perez-Navarro and colleagues at King’s College London sheds light on why. The team examined 33 years of grassland succession data in Minnesota, testing these hypotheses at two unusually fine spatial scales: neighbourhood plots of 0.5 m² and site transects of 40 m². This methodological choice proved decisive.

At the neighbourhood scale, where plants interact directly, practical features such as height and leaf structure mattered most. Species that differed in these traits were more abundant, supporting the limiting similarity hypothesis. Competition, it seems, rewards difference. Yet at the larger site scale, environmental filtering dominated. Here, species more similar to the community – those sharing traits suited to local conditions – were favoured, aligning with preadaptation.

Intriguingly, evolutionary closeness told a different story. Introduced species that were close to natives in the “family tree” thrived at both scales, reinforcing preadaptation even where trait-based analyses suggested otherwise. This disconnect between evolutionary lineage and physical features highlights a key insight: these two measures are not interchangeable.

The study also revealed nuanced differences between native and introduced species. Introduced plants tended to prosper with lighter seeds, higher leaf dry matter content, and in nitrogen-rich soils, suggesting distinct strategies for colonisation and resource use.

What does this mean for invasion ecology? First, spatial scale matters – profoundly. Analyses at tens of metres, often deemed “local”, may obscure competitive dynamics evident only at sub-metre scales. Second, relying on a single measure of similarity risks misleading conclusions. Evolutionary relationships and practical traits capture different dimensions of ecological reality.

Beyond its technical findings, this research invites reflection on how ecological theory grapples with complexity. Darwin’s conundrum endures not because the underlying hypotheses are flawed, but because nature resists simple binaries. Community assembly is shaped by overlapping forces – competition, environmental filtering, evolutionary history – whose influence shifts with scale and context.

For practitioners, the message is clear: management strategies for invasive species must consider both the traits that confer advantage and the environments that filter them. For theorists, the challenge remains to integrate these insights into models that embrace, rather than flatten, ecological nuance.

In the end, the study reminds us that scale is not a backdrop but an active player in ecological processes. To understand why species succeed or fail, we must look closely – sometimes as closely as half a square metre.

Read more:

Perez-Navarro, Maria A., Harry E. R. Shepherd, Joshua I. Brian, Adam T. Clark, and Jane A. Catford. 2025. “ Evidence for Environmental Filtering and Limiting Similarity Depends on Spatial Scale and Dissimilarity Metrics.” Ecology 106(11): e70244. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.70244

Article originally posted on KCL’s Spheres of Knowledge