Alien plants are everywhere – but not all invaders behave the same

Alien plant invasions are accelerating worldwide, posing serious threats to biodiversity and costing billions in management. A recent study – led by David Gregory as part of his Masters at King’s and in collaboration with Matt White from the Victorian government – sheds light on how these invasions unfold across landscapes and why growth form matters when predicting and managing risk.

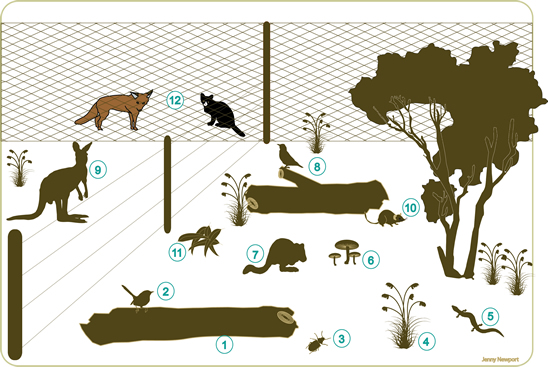

The research, conducted in Victoria, Australia, analysed data from more than 7,600 vegetation surveys spanning five decades. It found that 69 per cent of surveyed plots contained alien species, which made up 22 per cent of all recorded plant species. Forbs (broad-leaved herbs) were the most common invaders, followed by graminoids (grasses and similar) and woody plants. Yet the patterns of invasion were far from uniform.

Using boosted regression trees – a machine-learning approach well suited to ecological data – the team modelled how environmental, biotic and human factors influence both the presence and dominance of alien plants. Abiotic conditions, particularly temperature and rainfall, emerged as the strongest drivers overall, explaining up to 76 per cent of variation in invasion risk. Summer maximum temperature was a consistent predictor across all growth forms, with occupancy rising sharply above 23°C.

Human activity also played a major role. Areas with intensive land use, such as urban centres and agricultural zones, showed the highest levels of invasion. Alien forbs and graminoids were especially prevalent in these disturbed landscapes, often reaching more than 70 per cent cover in towns and cities. Alien woody plants were less widespread but still more likely to occur in urban areas than in intact forests.

Interestingly, the relationship between vegetation cover and invasion differed by growth form. Alien forbs and graminoids were more likely to occupy sites with high vegetation cover, but their proportional cover tended to decline as native vegetation increased – a sign of strong competition. Woody invaders, by contrast, were negatively associated with woody vegetation cover, suggesting that dense tree cover offers resistance to colonisation.

Spatial predictions confirmed these trends. Alien forbs had a high probability of occurring almost everywhere, even at higher elevations, though their cover remained low in alpine regions. Alien graminoids were largely confined to lowland areas dominated by human activity, while woody invaders were the most restricted, reflecting lower seed dispersal and availability and lower habitat suitability.

A global challenge

These findings resonate far beyond Australia. Invasive alien plants are among the top five drivers of biodiversity loss globally, according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

They disrupt ecosystems, alter fire regimes and threaten food security. Economic costs are staggering – estimated at more than US$400 billion annually worldwide – and rising as trade and travel expand. Climate change compounds the problem by creating conditions that favour invaders, while land-use change accelerates their spread.

Understanding invasion dynamics at scale is therefore critical for global conservation strategies.

The implications for management are clear. Maintaining and restoring native vegetation is critical to limiting alien plant dominance, particularly after disturbances such as wildfire – a growing risk under climate change. Urban expansion and agricultural intensification will likely increase invasion pressure, making strategic land-use planning essential. Grouping species by growth form, as this study does, offers a practical way to prioritise control efforts without building hundreds of single-species models.

Alien plant invasions are complex, shaped by climate, land use and ecological interactions. But by recognising both shared drivers and growth-form-specific patterns, we can design more effective strategies to protect ecosystems. Growth-form-based models provide a tractable, widely understood tool for science and policy – a step towards smarter, landscape-scale management of one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time.

Read more:

Gregory D, White M, Catford JA (2025) Similar drivers but distinct patterns of woody and herbaceous alien plant invasion. NeoBiota 103 31–52. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.103.164914

Article originally posted on KCL’s Spheres of Knowledge